Vietnamese Artists

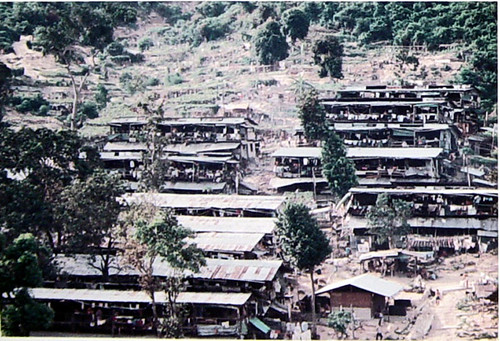

Working with Vietnamese refugees in Galang camp in Indonesia was one of the most memorable experiences of my 16 years career with UNHCR. From 1991 to 1993, I was the Technical Officer, responsible for the daily upkeep and maintenance of the Galang Camp infrastructure. At that time, there more than 15,000 refugees residing at Site 1 and Site 2 respectively.

During my time on Galang, I came to know Vietnamese refugees well. I especially enjoyed working with refugees attached to the Technical Office and a large number of support staff. The refugees were intelligent, innovative and, above all, hard working. Their often tragic circumstances and endured hardship, their individual performance, as well as the support provided to the camp communities by organisations including UNHCR and Camp authorities must be put on record. It was their resilience and belief in a positive outcome for their situation that kept them positively engaged, regardless of how difficult their predicaments were. I have tremendous respect for their forbearance.

When I was in Galang, it was a very hard period for many because of the screening process. Most of those who were there at that time had to prove they were genuine refugees when screened. Otherwise, they would be repatriated back to Vietnam. Many of them stayed in the Galang Camp as long as six years, and then were repatriated. Sadly, this often led to tragic outcomes as refugees chose to take their own lives rather than return. Many of these refugees were young. In fact, the Technical Office ran a carpentry workshop where coffins were made.

Generally, most of refugees had much time on their hands. There was hardly anything to do in the camp to keep their minds occupied and there was constant worry about their uncertain future. All they did was sit around, worry and wait. The psychological pressure was palpable. Keeping refugees occupied purposefully meant creating diversions from their worries, especially for the younger refugees.

One of the interventions that worked quite well was to find and engage artists. I love art and as I was told by my staff that there were professional artists among the refugees, I decided to give it a try. So, I spread the word that I was looking for artists. Soon, many came to see me, young and old. As a result, I assembled a team of the seven most promising artists. I provided art supplies and relevant literature or printed posters of the masters and they painted as part of their daily routine, engaged in art and enjoying working creatively. An art exhibition was held on Galang, which was also visited by various visiting delegations. Some paintings were sold and the proceeds given to the artists.

Among them was An Nguyen, who now lives in Western Australia. I will never forget our first encounter; An’s friend brought him to me. He was in his twenties and very shy. We exchanged a few words through an interpreter. He said that he had never painted before, but in his heart, he knew that he could paint. I was so touched by An’s words that I gave him a framed canvas of A4 size, a few brushes, oil paints and a copy of Dali’s masterpiece ‘Woman with a Head of Roses’. I asked An to come back in a week to show me how well he had managed to copy Dali’s painting.

Among them was An Nguyen, who now lives in Western Australia. I will never forget our first encounter; An’s friend brought him to me. He was in his twenties and very shy. We exchanged a few words through an interpreter. He said that he had never painted before, but in his heart, he knew that he could paint. I was so touched by An’s words that I gave him a framed canvas of A4 size, a few brushes, oil paints and a copy of Dali’s masterpiece ‘Woman with a Head of Roses’. I asked An to come back in a week to show me how well he had managed to copy Dali’s painting.

Seven days later, An came to the Technical Office, holding something behind his back. I shall never forget the look on his face. He appeared excited and nervous at the same time. I asked him to show me what he had brought with him. He hesitated for a moment and then produced a small painting – an impeccable and beautifully reproduced painting. Yes, I must say that An’s first painting was a complete surprise. It was exact, color-perfect and very well painted.

From then on, An just loved to paint. He painted day and night with great passion. I used to visit him occasionally at Site 1, where his tiny hut was located, to take a look at his artworks. An lived in a small hut about 3 by 4 metres in size, which he shared with his young wife, mother-in-law and sister-in-law. While painting, he sat on the ground in a tiny space between two beds. During the night, he used candles and a small oil lantern for light to paint, surrounded by hundreds of buzzing mosquitoes. An produced a set of the most beautiful copies of Dali’s best known paintings.

A year after I left Galang, An and his family, were accepted for resettlement in Western Australia. When he arrived, he contacted me and since then we see each other occasionally. As I kept An’s paintings, I showed him the paintings he had completed while on Galang. Knowing how much these paintings mean to him, I decided to return all of them to him. He was touched and very emotional when he took them back. These are not just paintings but vivid memories of a difficult and trying period during his early life and these paintings should be kept by An, for his children to appreciate when they grow up. They are also a manifestation of a personal struggle and hardship in a refugee camp that must not be forgotten.

It was a special experience to have met the Vietnamese refugees in Galang. My time there as the UNHCR Technical Officer held many memories. It is fair to say that I, and the hardworking Vietnamese in Galang, fostered many wonderful relationships, which contributed much to the well-being of the UNHCR staff and the camp community.

I am grateful for their support and feel privileged to have met people like An.

Stane Salobir

This story excerpted from the book "Boat People, personal stories from the Vietnamese exodus 1975 -1996" edited by Carina Hoang

Related Articles

SOS! You and God save us

When I recall the tragic refugee stories of danger, death, piracy, rape and loss of money, my heart is broken still. But on the other hand I had a happy time working with the unaccompanied minors, and a very meaningful time.…