The Floating Prison

By: Jon Davison

In 1979, the ‘Skyluck’, a 28 year old freighter, appeared overnight in Hong Kong packed full of Vietnamese refugees. The refugee camps were bursting at the seams and had nowhere to place them. The final outcome was not what anyone expected.

In early February 1979, officials at Hong Kong’s Refugee Control Centre (RCC), Police and Immigration services were breathing a sigh of relief after their long and drawn out saga with the ‘Huey Fong’. This rusting hulk of a ship had anchored off Hong Kong Harbour in December 1978 with 3,318 refugees on board seeking freedom from their war-torn homeland.

It had taken one month to figure out how to deal with the ship’s hungry, sick and helpless refugees, all who had paid nearly $3,000 in gold to the Vietnamese authorities for their passage.

Permission was eventually granted for the Huey Fong to sail into Hong Kong Harbour, and a mass of paperwork followed to organise temporary resettlement of the refugees at the old RAF station at Kaitak. This was at a time when Hong Kong was already bursting at the seams with up to 58,000 refugees from the small ships that were coming in daily. But these large ships were a different matter. For the exhausted RCC, Harbour Police and Immigration staff, their job was over, having successfully helped a large ship-load of refugees find safety.

The outcome of this exposed a lucrative people smuggling industry. Huge profits, upward of nine million dollars per ship, were being made by exploiting these refugees. The bigger the ship, the greater the profit and, due to the ‘Huey Fong’ scenario, Hong Kong was being seen as somewhat of a ‘soft touch’.

It was, however, a total surprise to all when, three weeks after the Huey Fong saga was settled, the Harbour Authorities woke to the sight of a large unfamiliar ship at anchor at the Western District Quarantine (WDQ) area. Frantic phone calls to the police on the Waglan and Green Island lookout stations that monitored all incoming vessels revealed that ‘a’ ship was signalled but did not respond. When the Harbour Police boarded the Skyluck they were stunned to find the ship was carrying 2,561 refugees in its holds, and, again, the refugees had each paid up to AU$3000 in gold for the journey. The ship had no papers or log book, although it did have a captain who told them that the ship had come from Singapore but, when questioned, would not give any more information about why the journey had taken twenty-seven days instead of the normal five days.

The authorities were starting to realise that this refugee problem was just the tip of a huge iceberg.

Though this new ship appeared to be in better shape than her decrepit predecessor, and her refugees were healthier, nevertheless, Skyluck was a freighter, not a passenger liner. The refugees were packed in its hold like sardines and crammed on the deck above, using crushed cardboard boxes to protect them from the harsh metal of the ships’ holds. It was certainly no place for women and children, although they were healthy, for now. The officials were once again faced with a huge problem of what to do with this number of people.

The authorities felt that the Skyluck episode should not be a problem that South East Asia had to deal with alone, but that it was a global responsibility. It was decided that the Skyluck should be towed to Lamma Island and anchored there until ‘something happened’, while the press stirred up the international conscience. In the meantime the refugees had to be fed and watered, their health had to be monitored, and the whole situation managed with care. Initially 5,400 lbs of provisions and 150 tons of water were given to the helpless refugees; it became an on-going process.

Once the immediate concern over the safety of the refugees was in hand, focus turned to the captain and crew of the Skyluck and their story. Where had the ship been for twenty-two days? The Taiwanese captain said he joined the ship in Singapore and had picked up all the refugees from their overcrowded, sinking wooden boats on the open sea. He alleged that following taking them on board, the refugees had tied him up at knifepoint and ordered him to sail into HK harbour. He added that the refugees had thrown all his log-books overboard, so he could not provide any written record of the ship’s movements. Still, the authorities questioned why it had taken him twenty days to sail from Singapore. There was no documentation about the reason for a hold full of cardboard boxes and the normal procedure of advertising the ship on all shipping lists of expected arrivals into Hong Kong had not been followed. The captain could give no explanation and what he offered simply did not add up.

The authorities started communicating with other ports the Skyluck may have visited along the route trying to find clues. However, most of these locations had actively pursued the ‘push back’ system of towing the refugee boats back out to sea, not permitting them to make landfall anywhere along their coastline, leaving them to fend for themselves, This system was policed aggressively and so the authorities did not hold out much hope of getting any facts. Finally, word came in from the Philippines that a freighter, the ‘Kylu’ had dumped 600 refugees on Boayan Island off Palawan, before being chased off by the Coast Guard. The Harbour Police discovered, by accident, that if the letters Sck were added to ‘Kylu’, it became ‘Skyluck’; it was so simple. This was confirmed when it was found that the name Skyluck had been applied on the bow over fresh paint. It was now confirmed that ‘Kylu’ and ‘Skyluck’ were the same ship. This presented strong evidence of people trafficking; it was the Huey Fong experience all over again. At the time, it was unheard of and beyond belief, that a nation would try to profit financially from its own displaced people.

The refugees were unaware of this. They had paid with their life savings, believing that their authorities were helping them escape the war and were finding them a safe and secure haven. Once on board the ship, they quickly realised their predicament, but it was better than going back and facing jail, or the retraining camps, or being killed. In the meantime, the authorities had to find out who was behind the illegal human trafficking. Although the Skyluck was registered in Panama, it was owned by a local shipping company in Kowloon (though they owned only one ship). So part of the problem appeared to be right on their doorstep. To try to solve the puzzle, court hearings and police questioning took place almost weekly; still nobody was talking.

Over time, the facts were revealed. The journey had started from Bến Tre Harbour in Vietnam, where 3,466 people had paid in gold taels to sail through the open sea on the 3,506-ton Skyluck. Tael is the official unit to measure gold throughout Asia, especially in Vietnam and China.

At the time, 1979, a tael of 24K gold was equal to $350 US dollars, and the price to board the Skyluck for adults was 12 taels of 24K gold leaves each. Children between the ages of 5 and 15 had to pay 1.5 taels of 24K gold leaves, and children under 5 paid 1 tael of 24K gold leaves. So the average family of five would have had to pay between $8,000 and $10,000, and for most this would have been their life savings. Considering that, for many, it may have been their third attempt to escape; the high cost of their efforts can be appreciated.

Upon leaving Vietnam, the name Skyluck had been repainted to read KYLU, a Panamanian registered rusty freighter. After dropping 600 refugees at Palawan, the crew changed the name back to Skyluck for its journey to Hong Kong.

It was not difficult to convince refugees that life aboard ship was not all that bad and better than life on shore in the refugee camps. Yet this was not the case. The problem was that most of the refugees were from towns and farms, with little or no affinity or experience with the sea. Many had never left the village they grew up in and had never seen the sea or a huge metal ship.

When you consider that one month at sea on an ocean liner is about as much as most people can tolerate, even with all the essentials such as good food, warm clothes, beds, relaxation, space and relative freedom. However, despite all these comforts you still have to contend with the smells of the ocean, fuel vapour, salt air, paint, nausea, the swell of the ocean and storms to name a few. Therefore, it would have been impossible to imagine one hundred and fifty-five days aboard a freighter, living in cardboard boxes, with no sanitation, and no private space.

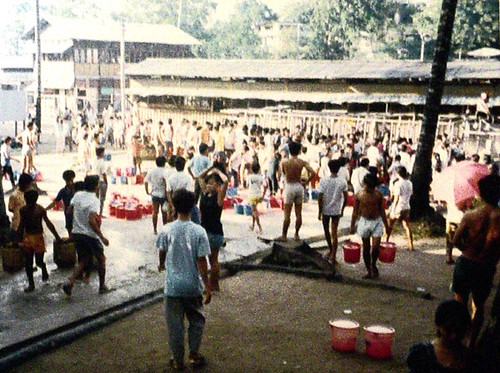

It was common knowledge that it was only a matter of time before something broke the stalemate. Would it be the police getting a breakthrough in their questioning of the captain and crew, or would world opinion intervene and offer a solution? It was neither of these; the patience of the refugees snapped. It started when groups of refugees jumped over the side, trying to swim to Lamma Island. Then more than four hundred descended the gangplank to get to the pontoons moored alongside the Skyluck. They had placards and crudely drawn signs demanding to be put ashore, to be given permission to send and receive letters and to be able to contact the UN. These were just a few of the demands. The authorities could see that the situation was explosive.

The leaders of the group of refugees were informed that they were illegal immigrants and charges would be pressed. Considering what they had all been through, this did not seem to bother them too much. However, when they realised that if charges were pressed no nation would accept them, and they would have a criminal record, they all agreed that patience and discipline were preferable to rioting. So order was restored again for a few months. To give them credit, the refugees were also acutely aware that the people of Hong Kong, although sympathetic to their predicament, knew that large amounts of funding were being diverted to them, rather than being spent on essentials like housing and improving social conditions in Hong Kong. Partly because of this understanding, the local communities were sympathetic to the refugee plight, realising that they were much alike.

But by June, five months later, on a perfect, sunny day, the Skyluck was seen drifting; its anchor chains had been severed deliberately. The ship eventually smashed on to the rocks on Lamma Island, its back broken. The refugees had had enough. A bold move indeed, and in doing so the refugees had taken their lives into their own hands. The ship could have been dashed on the rocks elsewhere with the loss of many lives. While condemning their actions, one cannot help feeling sympathy for these men, women and children who had just spent 155 days aboard a rusting hulk of a ship.

Now the authorities had to do something. A massive rescue operation was started at once by the Secretary for Security, the Harbour Police, the prison Commissioner and other authorities. As the tired old ship started taking on water, she listed to one side, and streams of refugees started pouring off the ship and clambering up the rocky, bush covered slopes of North East Lamma Island.

The authorities managed an almost impossible feat, from 0900hrs when they heard the anchor chains were cut, till midnight, all 2165 refugees had been transported to Chimawan Camp on Lantao Island. It was not until September that year that the first group of Skyluck refugees departed Hong Kong for their new life in the US.

The Skyluck was used as a bargaining chip in the business of ‘trafficking human cargo’ for huge profits by nations without a conscience. The ship was used by the Hong Kong government to discourage others, by stating that you cannot sail a large vessel into another nations waters, and simply ‘dump’ your human cargo, expecting that nation to take up to three thousand souls willingly. It made everyone look at what made people leave their home country and take to the sea in unknown boats of dubious seaworthiness; it is not something normal people do lightly. The point was that these people could no longer live in a country where their men were forced to submit to detention camps and to give in to an ideology.

In one sense, it was almost as if the Skyluck had one last mission before she came to the island to die. Her human contents could take no more, and broke. By destroying their floating prison, they broke the stalemate. The sinking of the ship meant her human cargo could at last be released. A nationwide famine, an unjust and ludicrous land reform, total war, the loss of one nation now split in two, and a brutal communist regime all combined to form the largest exodus in modern history. The Skyluck was just one vessel from this vast migration, but it became a symbol for what prompted the Vietnam War: a nation, bursting with a desperate need for freedom, whose people had been manipulated, destroyed and held prisoner for too long.

Out of the misery and trauma of this episode, and having no choice but to survive, the refugees formed a common bond. They were now and forever ‘Skyluckers’. It was an unforgettable journey in every respect. It stripped everyone to the bone where rank and position no longer meant anything. It was an equaliser that gave them humility and a common belief that anything was possible. It was the ultimate ‘test of life’. The ‘’Skyluckers’ are now dispersed throughout the globe. As a result of this episode, one thing was realised above all else – that people smuggling racketeers could not be stopped by punishing their innocent victims.

In 1980, the hulk of the Skyluck was finally re-floated and towed from Lamma Island to a ship wrecking company at Tseung Kwan O, or ‘Junk Bay’ in Hong Kong’s New Territories. There, over a period of three months, she was broken up for a scrap value of about 500 thousand HK dollars.

The 3500 ton ‘MV Waimate’ was commissioned by the Union Steamship Company of New Zealand in 1951, and built by the Henry Robb Shipyard in Leith, Scotland, as a K class vessel with the ship number 398. Following NZ service and a few changes of name such as the ‘Eastern Planet’, Skyluck Steamship Company of HK bought her from a Filipino company. SSC had only one ship registered; the Skyluck. Following the sale to the SSC, the Skyluck was on regular schedule sailings between HK, Taiwan, Indonesia and Bangkok.

Jon Davison

SOURCES & RESEARCH

Talbot Bashall – Personal diaries

John H. Grieve ‘Three days in the life of the Skyluck – 1979’

Hong Kong Government Information Services – News clippings 1979

The Hong Kong Star – various newspaper stories 1979

Photo of MV Waimate in Apia 1961, courtesy New Zealand Ship & Marine Society (http://www.nzshipmarine.com)

Photo: MV Waimate in Auckland NZ – courtesy of Stephen Chester, photographer.

This story excerpted from the book "Boat People, personal stories from the Vietnamese exodus 1975 -1996" edited by Carina Hoang

Related Articles

A Cluster of Pickerel Weeds

Time has gone by quickly. It has been 21 years living in this new country where our children have grown up. I have often told them the story of our trip, including the selfishness of that young man. I often remind myself that we must try hard to make the former “cluster of pickerel weeds” enrich this land which is our second homeland.

The girls, the girls! Hide the girls!

We were old enough to hide ourselves, and we jumped up at once and scrambled to a place where they could not see us. There were two of them, and through my seven-year-old eyes I could see they were armed with swords that gleamed mercilessly in the sun as they jumped onto our boat…

Live to Tell Our Tale

Since escaping Vietnam 25 years ago, my mind has constantly wandered back to two sisters – two of a dozen on my boat who were raped, tortured and stripped of their dignity. As a young man, I had never felt so helpless. I often wonder if those women have been able to get on with life.

My Mother

After the fall of Saigon, things changed drastically for our family under the communist regime. Wanting a better life for their children, my parents decided we would escape from Vietnam by boat, but not all together.

I Was Sixteen and I Was Lost

By: Lala Stein I had in my possession a little bag filled with memories and hopes. I was heading south, to Chau Doc, in the company of a small group of people with the same purpose: we were seeking freedom. After about a week in Chau Doc we managed to get on a ferry...

My Journey

By: Don Thu Nguyen When the communists took over South Vietnam I had just graduated from the military officer training school. Because I had not served in the military I was spared from going to re-education camp, but my background meant I had no chance of securing a...

My Children

By: Lyma’s mother For six months I lived on one bowl of salty rice a day. I was a prisoner, jailed because some policemen concluded I was a CIA agent because they found a photograph of me with an American. I explained that he had been my English teacher, and the photo...

The Endless Journey of An Exile

After the incident in 1975, there was a strong cross-border wave in Vietnam. There were many escapees who crossed the border by sea or by land, but the most common means of transportation was by sea…

Vietnamese Boat People in Australia

In April 1975, the North Vietnam Communist Government invaded South Vietnam. The Southern Vietnamese people could not live under the Communist regime so they later found their way for freedom…

Goodbye Grandma

Poor Grandma, she’d made the boat journey but could not survive once she got to the island. I carried her once more, this time to the jungle to bury her. She’d known that she might not make it…