My Experience with Refugees from Vietnam

By: Henry Ku

My experience with the Vietnamese Diaspora began in 1975.

On 30 April 1975, the South Vietnamese government collapsed and Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese army. People scrambled to get out. The world witnessed on TV the tragic and mad scramble to get on helicopters at the American Embassy. Some of us may still remember US sailors pushing a helicopter overboard from a carrier, probably, to make room for more refugees. Other Vietnamese fled the country in boats. They fought or bought their way on board anything that would float. It was a tragic and frightening event.

Four days later, on 4 May, about 4,000 refugees were approaching Hong Kong. They were people in little boats of all kinds picked up by the Dutch container ship, MV Clara Maesk. The next port of call was Hong Kong and, with very little notice, the problem fell to the Hong Kong Government.

The Hong Kong Government decided to allow the refugees to land. The plan was to put them in military camps vacated by the steadily drawing down of British forces. These camps were kept in good order and were ready to accommodate the new comers.

External security of the camps was assigned to the police while internal administration was entrusted to the Civil Aid Services (CAS), the civil defense corps of Hong Kong. The CAS was a general purpose agency, and, like all civil defense agencies of the world, its role was to deal with natural and man-made disasters. Members of the CAS were volunteers, trained to handle the demands of various types of emergencies.

As a CAS officer I was called out to prepare the Dodwell Ridge Camp in the New Territories. I was responsible for reception, which included registering refugees on their arrival, setting up beds in small huts and assigning the refugees to these huts.

We arrived on Sunday morning. The camp was not large and the huts, each about twenty by twenty-five feet, were situated in tight clusters. Each hut held seven or eight camp beds. Since we had no idea how many refugees would be coming, we had to make maximum use of each hut.

By late afternoon we had everything ready. We waited as the hours slipped by until about midnight, when the refugees started to arrive in government trucks. I knew from experience that each truck usually carried twenty-three persons. Luckily May was not very hot and the rainy season would not start in another month. The night was cool and clear; there was enough light to see in the parade ground to which they were first guided. They were orderly, lining up quietly and moving when their turns came. Because some of the refugees were Chinese communication with them was not difficult. After registration, we issued them with little cards on which their hut numbers were written. They were led to a cafeteria where a small contingent of British soldiers had prepared some simple meals for them. My concern was to get them into their huts as soon as possible.

My impression was that they were of reasonably good spirits, but they looked tired, which was understandable for they had travelled a long way and it was past midnight. We were tired, too, for some of us had been on duty for close to twenty hours. Finally, some time close to dawn, things quietened down.

This was the first time I came across people fleeing from war, and I had never witnessed any such sorry plight. There were two things I definitely learned.

If you were not prepared when you had to run, you ran away empty handed. There was no time to pack.

(ii) Your family is the only thing that matters.

Regarding my observation that family is our primary concern, there were times when we had to break up a family because most of the beds in a hut had already been assigned. Despite all our assurances that a family member might be in the next hut, just five steps away, the family would beg to be allowed to wait for another hut so that they could remain together. Of course, we complied with the requests. The moral of the story: in times of extreme distress, your family is all you have and you would fight all the powers under heaven to keep it together. I did not appreciate that until much later when I became an immigrant myself. My family and my siblings kept me going when I almost lost heart.

After two weeks, the central government found that it could not man the control centre interminably in the manner of an emergency. Through an arrangement between various agencies, I was given twenty-four hours notice to leave my regular posting to take up the position of what eventually became Controller, Refugee Control Centre. For about four months, I worked in a windowless office from 8:00 am to 6:00 pm, Monday to Saturday, never seeing the sun and surrounded by a sea of telephones and other communication devices.

Then resettlement began. The countries that offer opportunities for resettlement were notably the US, Canada and Australia. I was told that the Australians were the best organised and even sent Vietnamese speaking staff. By August 1975, most of the refugees had left Hong Kong. The work tapered off, and the camps started to close down. As there was not much work for me I asked to be posted back to the real world.

Emergency Again – The Boat People Saga

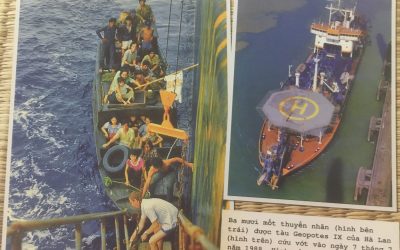

In the late 1970s, the Vietnamese government decided they would ‘encourage’ people they did not want to leave Vietnam. In the north, the unwanted people had to walk to China through the ironically named Friendship Gate. In the south, refugees got hold of little boats and went out to the open sea trying either to sail to some safe haven or wait to be picked up by passing ships. Not all the countries in the region were willing to receive these refugees. Also, in some cases, schemes were organised by heartless racketeers who bought old ships, painted them over and took on refugees who could pay, restricting each of them to a space of a few square feet. This episode of human tragedy came to be called the Vietnamese Exodus or the Boat People Saga. In 1980, a total of 75,000 of these boat people sailed into the Hong Kong Harbor.

In the late 1970s, the Vietnamese government decided they would ‘encourage’ people they did not want to leave Vietnam. In the north, the unwanted people had to walk to China through the ironically named Friendship Gate. In the south, refugees got hold of little boats and went out to the open sea trying either to sail to some safe haven or wait to be picked up by passing ships. Not all the countries in the region were willing to receive these refugees. Also, in some cases, schemes were organised by heartless racketeers who bought old ships, painted them over and took on refugees who could pay, restricting each of them to a space of a few square feet. This episode of human tragedy came to be called the Vietnamese Exodus or the Boat People Saga. In 1980, a total of 75,000 of these boat people sailed into the Hong Kong Harbor.

The Hong Kong Government had to create a system to deal with the emergency. I was recruited by the then Deputy Secretary for Security assigned to this special task. I had worked for him in another emergency, so we were familiar with each other’s way of working. I filled a position that was eventually titled, Chief Executive Officer (Refugees). I must make it clear that I was not the man in charge. The problem was so overwhelming that we were all learning to cope as we went along. We only knew that we had to land the refugees quickly because by August 1980, there were thousands of these people floating in derelict little boats in the harbour. The highest number for this floating population, I always remembered, was 8,383. God was kind to us all; that year, no typhoon threatened Hong Kong. If we’d had so much as a puff of wind, many of the little boats would have capsised and thousands would have perished.

The Refugee Division was organised into two parallel units. The Refugee Control Centre (RCC), which dealt with operational matters such as landing arrangements, transporting refugees, keeping tab of arrivals and departures and other statistics. The Centre had the functions one would usually associate with a communication centre. Talbot Bashall was the Controller and he had a few assistants.

The rest of the administration, including planning and setting up camps, liaising with internal and external agencies, feeding, controlling funds, servicing and maintaining camps, matters of health and hygiene, and social services, etc., were entrusted to my team of four people. I headed the team, very ably assisted by three senior executive officers. We did not have a fixed schedule of duties. Flexibility was the order of the day. Whoever happened to be available would deal with whatever was required of us. And we faced a wide variety of demands. Apart from the usual activities, we had to deal with lice infestation, sewage blockage, fire hazard education, medical emergencies, and even finding quarters for some volunteers.

My team and the RCC staff had food and bedding in the office ready to work long hours. Luckily, we never had to work overnight, but at times we worked till very late into the night. It was a taxing time for us all and, at times, it would really test one’s faith. I remember one day when we had one of those monsoon downpours, four of us stood on the veranda outside our offices and, as we watched the sheets of rain coming down incessantly, we thought of the misery of the refugees in the little boats. A question came up: was there a god? If there was, why would god allow such suffering? What was the purpose? One of us said, “Of course, there is no god otherwise we would not be here doing this job!” Luckily, the sad experience did not shake our faith. One of us remains to this day a leading member of the Hong Kong Catholic diocese and another is a deeply devoted Buddhist, and I still go to mass every week.

It was most remarkable that, amongst all of us, there had never been a quarrel nor had voices been raised in anger. Instead, a strong sense of camaraderie and humor was the motivational force behind us. At times we all gathered at Talbot’s control centre to commiserate with one another over frustrating events or had a good chuckle when things went well. Eventually we all got transferred out and each went his own way, but we left with a deep sense of friendship. Even to this day we still keep very close contact with one another through e-mail and Skype.

The work was unusual to say the least. Just to paint a picture. The Civil Aid Services (CAS) was responsible for feeding refugees still floating in their boats. At the height of the influx, it took a CAS team ten hours to distribute food to refugees. I asked why it took so long. I was told that each boat had to row to the distribution point – a pontoon in a corner of Victoria Harbor. Unlike cars there were no brakes in a boat, to stop it on a dime as the saying goes. So, time was needed for the boats to manoeuvre back and forth to line up with the pontoon. Some of the boats were so derelict that when water was delivered to them, pumps and water hoses could not be used for fear that the force of the water coming out of a hose would sink them.

The food was cooked by the Hong Kong government kitchen staff that normally catered for local victims of fire or natural disasters. One day, I visited the kitchen and was utterly amazed by the cooking set up. The staff used four gigantic woks to cook the food. Each one of these woks was about ten feet in diameter. It was like a sunken bath. The cook walked around the wok’s edge, which had a cement walkway. He turned over the vegetables in the wok with a round tipped shovel. The food, when cooked, was placed in wooden tubs and delivered to the sites by the CAS. Every week, a supplementary package was issued to each refugee, irrespective of age. This package contained items such as condensed milk, candy, fruit, crackers, cookies, peanuts. The purpose of the package was to ensure refugees had a supply of balanced nourishment.

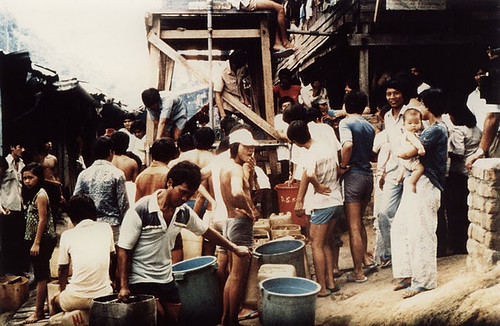

The camps were crowded. One of them was run by the Christian Council, another by the Red Cross; others were run by Caritas, the YMCA and by the Hong Kong Government. At that time, they were ‘open’ in the sense that refugees could go out to work, and they did take advantage of it. Some even sent their children to local schools. In other camps, because of their remote locations, camp managers arranged for work to be delivered to them from factories. Some made quite a bit of money in the factories. In fact, we had very unusual complaints regarding refugees; airlines complained that they had too much luggage when they eventually left for their final destinations.

Each camp had a medical clinic and one also had a dental clinic. Here I must give credit to all the voluntary and charitable organisations that came to help in the camps: The Christian Council, Caritas, YMCA, Red Cross, Save the Children Fund, World Vision, the Salvation Army and the

International Rescue Committee to name a few. There were many doctors, nurses, and others who came from all over the world, running schools and childcare centres, helping out in the camp clinics, and providing other social services. The scouts (here I pulled some strings) went to one of the camps to set up a troop for the young people, providing free uniforms and equipment. Some of the government employees came back during their off-days to run classes and activities for the children. The world was simply full of good people.

Because I had served in many parts of the government and had good relations with the staff, it was easy for me to get things done. When Save the Children Fund wanted to modify a van for use as a small ambulance, or when the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) wanted to transport an X-ray van to Macao, I was able to link them up with the right people. My team even wrote a manual called Refugee Camp Manager’s Handbook. A few years later word got to me that the UNHCR had asked for it because they wanted to send a copy to Japan, which was just beginning to experience refugee problems.

My service with the Refugee Division was one of the most gratifying experiences in my whole working life. I cannot list all the things I learned during the two and half years. It changed me as a person and changed my career.

Henry is retired and currently lives in Hawaii

Henry Ku

This story excerpted from the book "Boat People, personal stories from the Vietnamese exodus 1975 -1996" edited by Carina Hoang

Related Articles

A Cluster of Pickerel Weeds

Time has gone by quickly. It has been 21 years living in this new country where our children have grown up. I have often told them the story of our trip, including the selfishness of that young man. I often remind myself that we must try hard to make the former “cluster of pickerel weeds” enrich this land which is our second homeland.

The girls, the girls! Hide the girls!

We were old enough to hide ourselves, and we jumped up at once and scrambled to a place where they could not see us. There were two of them, and through my seven-year-old eyes I could see they were armed with swords that gleamed mercilessly in the sun as they jumped onto our boat…

Live to Tell Our Tale

Since escaping Vietnam 25 years ago, my mind has constantly wandered back to two sisters – two of a dozen on my boat who were raped, tortured and stripped of their dignity. As a young man, I had never felt so helpless. I often wonder if those women have been able to get on with life.

My Mother

After the fall of Saigon, things changed drastically for our family under the communist regime. Wanting a better life for their children, my parents decided we would escape from Vietnam by boat, but not all together.

I Was Sixteen and I Was Lost

By: Lala Stein I had in my possession a little bag filled with memories and hopes. I was heading south, to Chau Doc, in the company of a small group of people with the same purpose: we were seeking freedom. After about a week in Chau Doc we managed to get on a ferry...

My Journey

By: Don Thu Nguyen When the communists took over South Vietnam I had just graduated from the military officer training school. Because I had not served in the military I was spared from going to re-education camp, but my background meant I had no chance of securing a...

My Children

By: Lyma’s mother For six months I lived on one bowl of salty rice a day. I was a prisoner, jailed because some policemen concluded I was a CIA agent because they found a photograph of me with an American. I explained that he had been my English teacher, and the photo...

The Endless Journey of An Exile

After the incident in 1975, there was a strong cross-border wave in Vietnam. There were many escapees who crossed the border by sea or by land, but the most common means of transportation was by sea…

Vietnamese Boat People in Australia

In April 1975, the North Vietnam Communist Government invaded South Vietnam. The Southern Vietnamese people could not live under the Communist regime so they later found their way for freedom…

Goodbye Grandma

Poor Grandma, she’d made the boat journey but could not survive once she got to the island. I carried her once more, this time to the jungle to bury her. She’d known that she might not make it…