In Memory of Mong Ha

By: Carina Hoang

“No more worries, no more sorrows,

No more hurt and no more pain,

In the kingdom of Heaven you now stand,

Our love for you will forever remain.”

‘Dovie’ Salaba

Late in the morning of 24 September 2009 our group arrived at Kuku, a deserted, jungle-covered Indonesian island where Vietnamese refugees found temporary refuge in the late 1970s and 1980s. As soon as everyone got off the boat, we headed for the forest. Although we’d been there just six months before, we almost got lost because the grass had grown so tall. We could barely see the path that led to the creek.

There were fifteen of us in the group, including local Indonesian villagers and military personnel from the Navy and Police departments. We divided into two groups and walked along the creek in opposite directions. It was only about five minutes later that I heard Alex call out: ‘Carina, up here. There are many graves.’ My group turned around, crossed the creek and climbed up the hill toward Alex. Soon we arrived at an open area in the middle of a dense forest.

We looked around and saw many graves, some of them still with gravestones. There was something quite eerie about the place – it was so quiet, the kind of stillness that demands your complete silence. The air felt cold and damp. There was hardly any sunlight: the area was surrounded by very large trees that might be more than a hundred years old.

My eyes rested upon a grave by the edge of the forest, one that looked different from the others. It had a thick band of rocks around it, held together by cement, and it was raised nearly half a metre above the ground. The centre was clearly hollowed, and it looked as if it had been dug up.

What had drawn me to the grave was its perfectly square gravestone. Though it was severely weathered, the letters were still deeply etched into it. My brother and I cleaned it with water. We traced the letters and made out the name, birth date and death date of the deceased. Her name was Nhan Thi Mong Haand she died at the age of fifteen. At about this same time I had also lived on Kuku, though I’d left the island a few months after she passed away.

Memories of thirty years before on the island came back to me. It was a horrible time: many of us suffered malaria and other tropical diseases, and someone was buried in the jungle almost daily. ‘This could have been me’, I thought, and felt a shiver pass through my entire body.

Our group cleaned and painted gravestones wherever we found them, and took photographs of them. As soon as we returned from the trip, I posted on my website photos of the graves that we found, and sent out emails to as many people as I could, hoping that someone would recognise them. Somehow, a journalist got hold of the email and decided to publish the story in a Vietnamese Newspaper in Los Angeles.

A week later I received a telephone call from a Miss Thanh, who lives in France. In a shaky voice she said: ‘Miss Carina, grave number 20 on your website was my sister’s. My parents and I were shocked to see the picture after thirty years …’ Thanh stopped and cried for a moment, then she continued: ‘Last night we received so many phone calls and emails from friends who read your story in the newspaper and recognised my sister’s grave’. As she was speaking, I quickly checked my website, and to my surprise it was the grave of Mong Ha, the one whose gravestone my brother and I had spent quite a bit of time restoring. Then Thanh surprised me again when she said: ‘Carina, we were on the same boat, your family and mine. We were all on boat VT075’.

Thanh said there were five of them in her family group when they left Vietnam, but they lost two members during their flight. Her grandfather died from exhaustion as soon as he got off the boat; three months later, in the middle of the night, her little sister complained about a bad headache and gave her last breath after just a few hours.

An hour later I received a call from Thanh’s mother, who also lives in France. She must have got all the details from Thanh, as she did not ask as many questions about her daughter’s grave. But she cried a lot. I could feel her pain through her voice. She kept repeating: ‘My daughter was only fifteen – too young, too young’. Then she asked: ‘When are you going to Kuku again? Could I come with you? I want to see my daughter’s grave, I want to hold her …’ After she stopped crying, I explained to her that she might be too old to endure this kind of expedition. Thanh and her mother have kept in touch with me via phone and email since then.

During that same week other families also contacted me because they recognised the graves of their loved ones among the photos on my website. They were all anxious to revisit the graves and wished to bring the remains of their loved ones back with them. So I decided to make another trip to Indonesia in March 2010 to help these families. Unfortunately, Thanh had an operation scheduled for that time. I thought about rescheduling the trip, but as most of our travelling would be by boat we had to avoid the monsoon season, which would have meant delaying the trip for a year.

After consulting with the other families involved, I had to stay with the original plan. However, I offered to rebuild Mong Ha’s grave on behalf of her family. Thanh sent me a plaque with messages from her family to place on the grave, and her mother sent me a letter she’d written to Mong Ha and asked me to read it there.

A few weeks before the trip, I realised that the day we were scheduled to arrive on Kuku happened to be Mong Ha’s birthday, so I sent messages to her friends and family. I received birthday cards and presents for Mong Ha from her family, friends and teachers from many countries. On her birthday we offered her flowers, fruit, cards and gifts. We gathered around her grave, lit some candles and prayed for her. We all cried so much as I read the letter Ha’s mother wrote for her.

I hired three Indonesian men to re-build Ha’s grave. The weather was touch and go, and we had only a few days on Kuku, so the men immediately returned to their island to gather materials and came back very early the next day. It took them several trips up the hills to bring the tools, water, cement and sand to the gravesite. Their work was frequently interrupted by rain, and the next day, when they saw that the weather was not going to let up, they worked through the rain. All the raincoats and plastic sheets available were used to cover the grave as the men worked without any cover.

We finally finished Ha’s grave and had our last prayers for her before we left the island. We hope she is resting in peace, knowing that she is loved and remembered by many.

Carina Hoang

This story excerpted from the book "Boat People, personal stories from the Vietnamese exodus 1975 -1996" edited by Carina Hoang

Related Articles

A Cluster of Pickerel Weeds

Time has gone by quickly. It has been 21 years living in this new country where our children have grown up. I have often told them the story of our trip, including the selfishness of that young man. I often remind myself that we must try hard to make the former “cluster of pickerel weeds” enrich this land which is our second homeland.

The girls, the girls! Hide the girls!

We were old enough to hide ourselves, and we jumped up at once and scrambled to a place where they could not see us. There were two of them, and through my seven-year-old eyes I could see they were armed with swords that gleamed mercilessly in the sun as they jumped onto our boat…

Live to Tell Our Tale

Since escaping Vietnam 25 years ago, my mind has constantly wandered back to two sisters – two of a dozen on my boat who were raped, tortured and stripped of their dignity. As a young man, I had never felt so helpless. I often wonder if those women have been able to get on with life.

My Mother

After the fall of Saigon, things changed drastically for our family under the communist regime. Wanting a better life for their children, my parents decided we would escape from Vietnam by boat, but not all together.

I Was Sixteen and I Was Lost

By: Lala Stein I had in my possession a little bag filled with memories and hopes. I was heading south, to Chau Doc, in the company of a small group of people with the same purpose: we were seeking freedom. After about a week in Chau Doc we managed to get on a ferry...

My Journey

By: Don Thu Nguyen When the communists took over South Vietnam I had just graduated from the military officer training school. Because I had not served in the military I was spared from going to re-education camp, but my background meant I had no chance of securing a...

My Children

By: Lyma’s mother For six months I lived on one bowl of salty rice a day. I was a prisoner, jailed because some policemen concluded I was a CIA agent because they found a photograph of me with an American. I explained that he had been my English teacher, and the photo...

The Endless Journey of An Exile

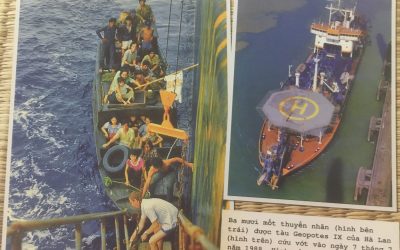

After the incident in 1975, there was a strong cross-border wave in Vietnam. There were many escapees who crossed the border by sea or by land, but the most common means of transportation was by sea…

Vietnamese Boat People in Australia

In April 1975, the North Vietnam Communist Government invaded South Vietnam. The Southern Vietnamese people could not live under the Communist regime so they later found their way for freedom…

Goodbye Grandma

Poor Grandma, she’d made the boat journey but could not survive once she got to the island. I carried her once more, this time to the jungle to bury her. She’d known that she might not make it…