The Fly Island

By Carina Hoang

I still don’t know how we survived it all. It is true that the human being is a remarkable creature, capable of great adaptation and having a strong survival instinct.

After the fall of Saigon, life became extremely difficult for my mother. My father was in a political prison and our house had been confiscated. She had to take care of seven young children, her mother and her mother-in-law all by herself. Because of my father’s military background we children were not permitted to attend high school, and so there was no hope for our future. Add to that the tremendous uncertainty of the situation: people were living in the constant fear of what might happen tomorrow.

Although many families in similar circumstances to ours had sent their children out of Vietnam, my mother did not have the heart to separate from her children, let alone send them away on their own. However, in late 1978 Vietnam and Cambodia were at war, and my mother feared that we would be sent to the battlefield and killed. Young people with our political background would surely be enlisted; it was only a matter of time. So she had to make the ultimate decision and let her children escape without her. My mother did not want to leave the country while my father was still in prison; besides, she could only afford to pay for three of us to escape.

I was sixteen when I joined the Vietnam exodus on 31 May 1979 with my sister and brother, aged twelve and thirteen, in a 25-metre wooden craft packed with 373 people, including 75 children.

During our first night on the South China Sea we struck a storm so violent that our boat felt like a cradle being rocked by angry hands. There was an indescribable mixture of sounds as children cried, adults screamed, the thunder roared and waves crashed on us. Every time it seemed our boat was going to be smashed up, more than three hundred Chinese and Vietnamese people, in different dialects and accents, desperately prayed to our various saviours – the Virgin Mary, Jesus, Buddha, ancestors. Never had I felt so vulnerable. I used to wake up in the middle of the night to the sound in my head of people chanting. No words could describe this resonance. After the storm we were left sitting in a slimy mixture of vomit, urine and seawater.

The second day was uneventful, and most of us just lay there exhausted. Slowly we regained our strength and started to clean up the mess.

On the evening of the third day we were prevented from approaching Malaysia. Military men fired at our boat, then jumped on board and stole our maps, compass and valuables. One of them pointed a gun at my brother’s neck and demanded his gold necklace. Then they tied our boat to theirs, towed us back out to the South China Sea, fired a few more rounds into the air, cut the rope and left us out there in the middle of the night.

On the fourth and fifth days, two groups of Thai pirates pursued us. Luckily, we got away. When they were chasing us, all the women and girls were sent to the bottom of the boat, where we smeared soot and rubbish over our faces and bodies to make ourselves as ugly and as smelly as possible, in the hope that the pirates would not want to rape us. Later I was told that, if we’d been caught, what we did would have made no difference: the pirates would have stripped us naked and hosed us down before raping us.

By mid-morning of the sixth day we were running out of water and food and had hardly any energy left. Our first casualty was a seventy-year-old man who died of hunger and suffocation. That evening we lost a seventy-five-year-old woman whose grandchildren found her dead sitting up with her knees drawn up to her chest, the position she’d been sitting in for the previous six days. Their bodies were wrapped in blankets and tossed overboard.

At last, on the eighth day, we reached a small fishing village on Indonesia’s Keramut Island, where our boat’s owners decided to sink the vessel so we could not be sent back to the ocean. The villagers must have felt overwhelmed – we outnumbered them three to one.

Three days later we were transferred to Letung Island and twelve days after that we made the long boat ride to Kuku Island. Excited at the thought that we would soon be placed in a refugee camp, I had hardly slept the previous night. But as we approached Kuku we could see no signs of huts or anything that looked like a camp. Only when we got ashore did we realise it was uninhabited.

Night seemed to fall quickly and nearly four hundred people had no alternative but to settle down on the sand between the ocean and the jungle. After dark there was a welcoming thunderstorm that soaked everybody. We shivered until the morning sun began to dry us out.

We were wondering if there had been a mistake, or perhaps someone would come back in the morning to take us to a refugee camp nearby. We waited all day, then the next day and the next day. Eventually there came the realisation that we were stranded. Indeed, we were stranded for nearly three months before aid came from the UNHCR. Initially we survived on coconuts, jungle fruit and vegetables, seafood – anything we could find in the jungle or in the ocean. Soon some villagers from nearby Indonesian islands came around with food they were prepared to exchange for items such as gold, jewellery or US currency. Those who did not have any valuables continued to search in the jungle. In order to feed the three of us, I sold the jewellery that my mother had given me and my sister.

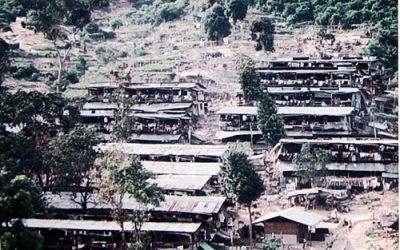

When we first arrived, some people-built huts from branches and leaves, especially if there were strong men among them who could go into the jungle and cut down trees. Not only did my siblings and I lack the strength to cut down trees and make a hut for ourselves, the only tool we had was a pocketknife. Eventually we shared a hut with two other families. We ended up living on Kuku for nearly nine months.

Carina Hoang

This story excerpted from the book "Boat People, personal stories from the Vietnamese exodus 1975 -1996" edited by Carina Hoang

Related Articles

My Experience with Refugees from Vietnam

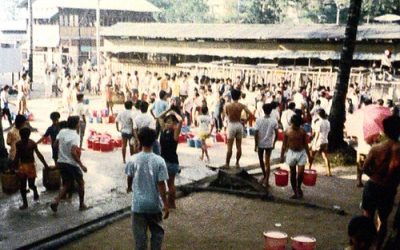

By: Henry Ku My experience with the Vietnamese Diaspora began in 1975. On 30 April 1975, the South Vietnamese government collapsed and Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese army. People scrambled to get out. The world witnessed on TV the tragic and mad scramble to get...

Vietnamese Artists

Working with Vietnamese refugees in Galang camp in Indonesia was one of the most memorable experiences of my 16 years career with UNHCR. From 1991 to 1993, I was the Technical Officer…

In Memory of Mong Ha

Late in the morning of 24 September 2009 our group arrived at Kuku, a deserted, jungle-covered Indonesian island where Vietnamese refugees found temporary refuge in the late 1970s and 1980s.

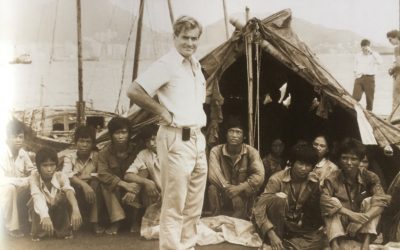

The Floating Prison

By: Jon Davison In 1979, the ‘Skyluck’, a 28 year old freighter, appeared overnight in Hong Kong packed full of Vietnamese refugees. The refugee camps were bursting at the seams and had nowhere to place them. The final outcome was not what anyone expected. In early...

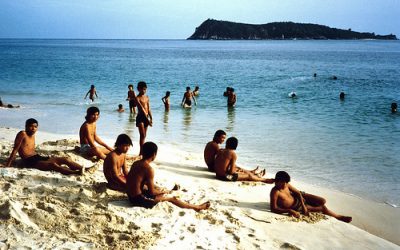

Young and Happy

By: Mimi Woznicki I enjoyed my time in the Indonesian refugee camp immensely. I was twelve-years-old and didn’t have a care in the world. Every day for ten months I couldn’t wait to get up in the morning and take a long walk along the beach collecting seashells and...

Compassion Fatigue

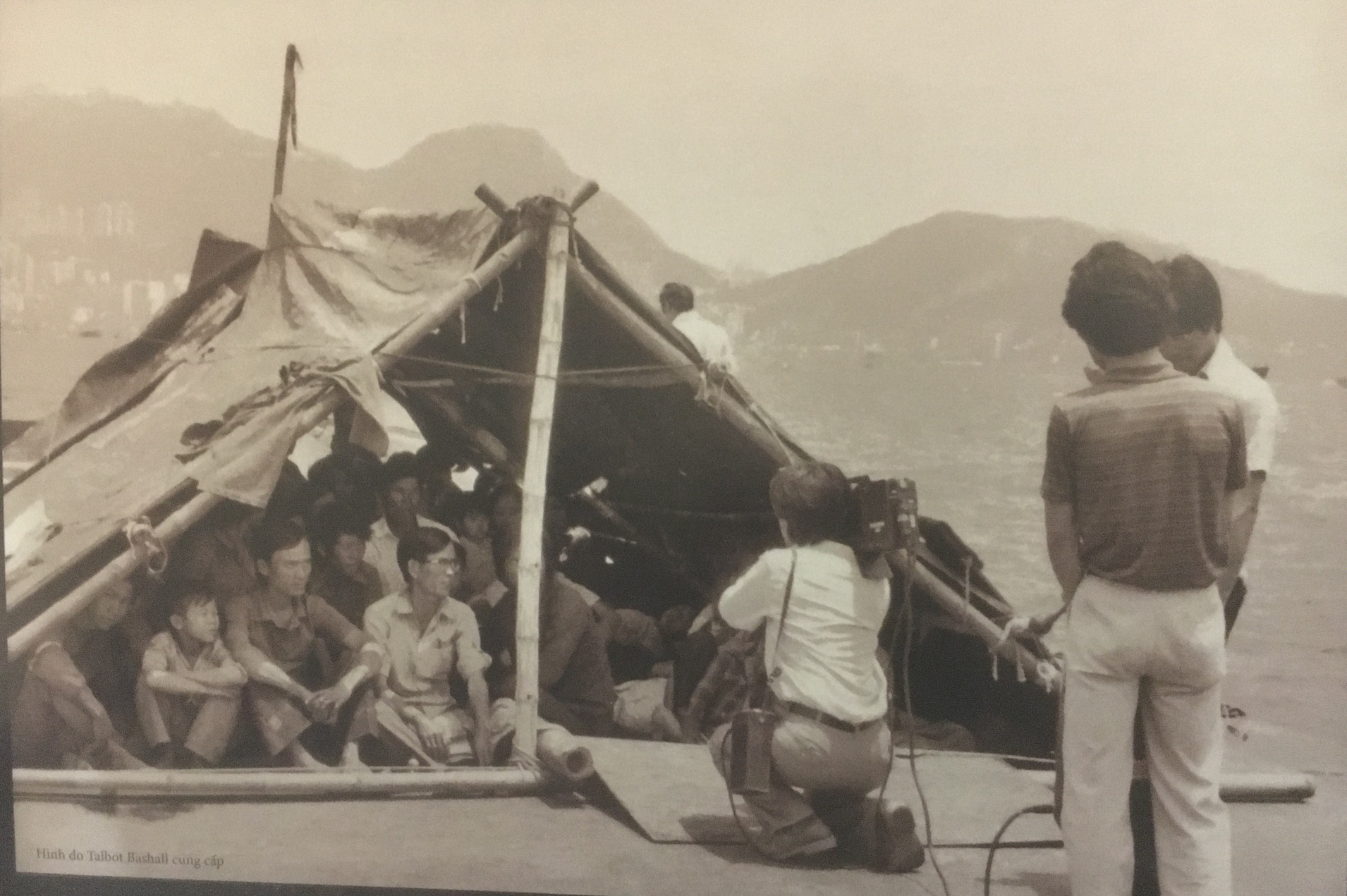

Talbot Bashall was Controller of the Refugee Control Centre that managed all the refugee camps in Hong Kong during the ‘Vietnam exodus’ years. He, more than anyone else, witnessed at first hand the vastness of this tragic exodus. He helped literally thousands of refugees to gain freedom. Talbot now resides in Perth, Western Australia.