Compassion Fatigue

By: Talbot Bashall

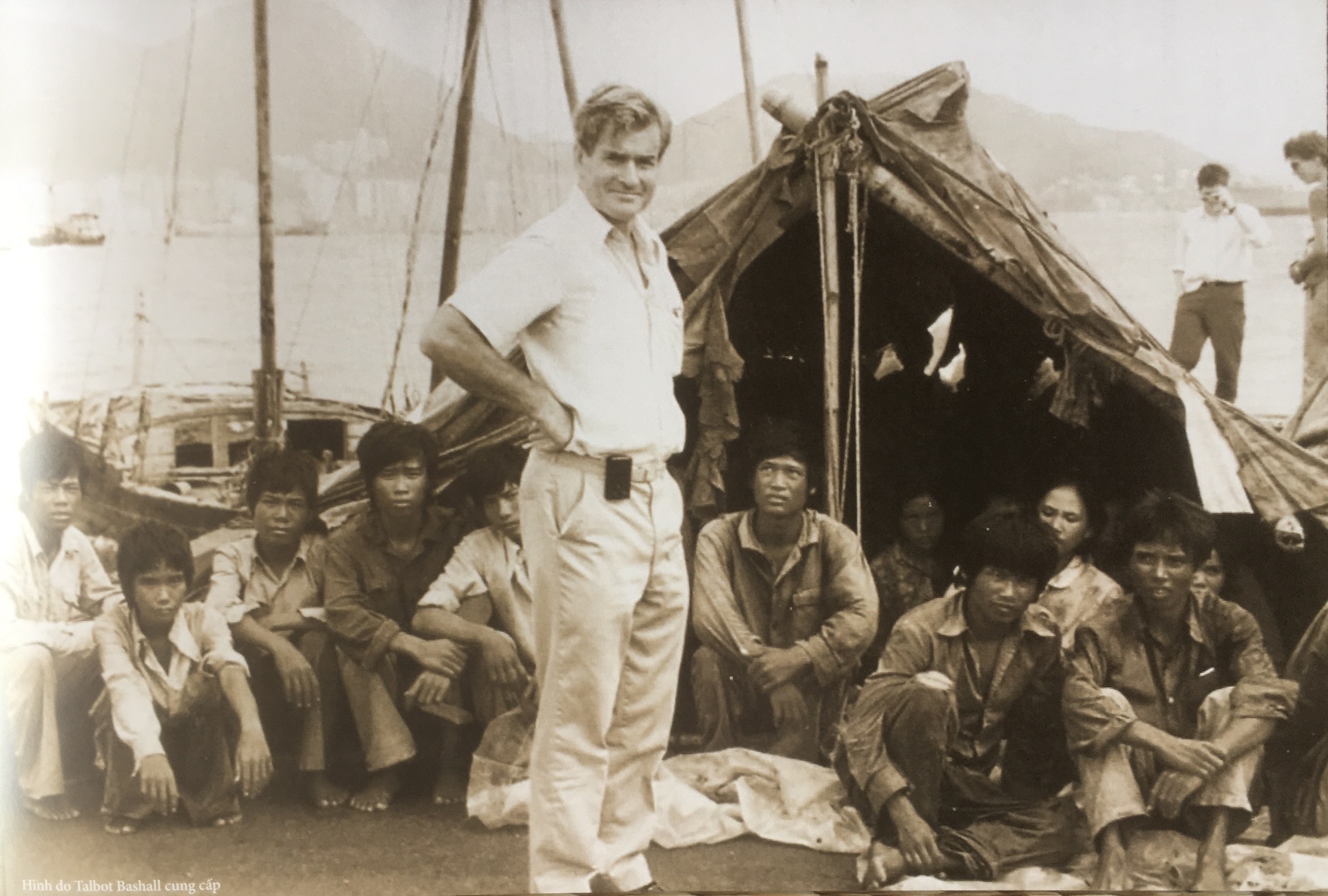

Talbot Bashall was Controller of the Refugee Control Centre that managed all the refugee camps in Hong Kong during the ‘Vietnam exodus’ years. He, more than anyone else, witnessed at first hand the vastness of this tragic exodus. He helped literally thousands of refugees to gain freedom. Talbot now resides in Perth, Western Australia.

At 9:15 on the morning of Wednesday 18 April 1979 I was summoned to the office of the Hong Kong Government’s Secretary of Security and given a synopsis of the Vietnamese refugee situation. Its essence was that an ever-increasing flow of refugees from Vietnam was feared to be imminent. Then it became clear why I had been called in: I was to be appointed Controller of the newly created Refugee Control Centre, with the task of coordinating all the efforts of the Hong Kong Government in dealing with the anticipated numbers and forging a working relationship with all the accredited consulates, especially those of the USA, the Netherlands and West Germany. In addition I was to liaise closely with the UNHCR (United Nations High Commission for Refugees) and all other relevant organisations, voluntary and otherwise, to ensure as far as possible the smooth handling of refugees and their subsequent dispatch to countries of resettlement.

Bearing the main brunt of the now rapidly developing crisis were the Police and the Immigration Service. Both organisations performed way ‘beyond the call of duty’, and their heroism, doggedness and unparalleled commitment were worthy of the highest praise. I hope this acknowledgement of their work and dedication may go some way towards compensating them for the fact that the accolades they deserved were never awarded.

At that time I recalled that, during a stint dealing with war crimes in Venice as a 20-year-old way back in 1947, I knew that I was living history, and in my new role I had the same perception. I remembered also something said by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Commander of all Allied Forces in Europe at the end of World War II (and later President of the United States), when he saw the Nazi concentration camps at the end of the war: ’Take as many photographs as possible, because some time in the future some SOB will say “It never happened”.’ So I took lots of photographs, encouraged others to do the same and, with the incredible cooperation of my wife, Cynthia, collected personal and official photographs, newspaper clippings and other relevant material. I could foresee that this Communist-directed holocaust would be either played down years afterwards or declared, by the successors of the perpetrators, as having ‘never happened’.

As part of my duties, my day would begin at 6 am and would go on until late in the evening depending on boat arrivals and whatever crises were developing. It was like nothing I had ever experienced before. There was no ‘rule of thumb’ for dealing with events as they unfolded.

I was to be on call, in modern parlance, 24/7. Indeed, I had not been at my new post five minutes before the action started. I was given a ‘pager’, the predecessor of the mobile telephone, a benighted thing that would ‘beep’ and convey messages from all points of the compass telling of boat arrivals and a myriad of crises associated with camps, their administration and other matters. My office was located in the then Victoria Barracks – now demolished and replaced by high-rise offices and hotels – and I was told to get on with it.

Cooperation with the various organisations was not in the least difficult, as a strange feeling of camaraderie pervaded the whole scene. All were totally committed to the easing of this dreadful calamity. As each boat arrived my beeper would sound the alarm and I would log the information and convey it ‘up the line’. These boats were intercepted and escorted to the WQA (Western Quarantine Anchorage), where they were subjected to health and security checks. While at WQA these poor, wretched, bewildered and totally traumatised pieces of human flotsam were provided with basic medical help and fed and watered. Then after seven days they were towed in and disembarked at the Government Dockyard. This comprised a ‘landing jetty’ with a huge dilapidated ‘go-down’ behind it. That vast structure, due for demolition, lent itself admirably to coping with the drama as it unfolded. To give some idea of the vastness of our problem, I note that on 12 July 1979 this site held 12,179 men, women and children.

As my daily diaries and logs recorded, conditions in this building were far from ideal – a leaking roof and generally primitive conditions – but it would have been a source of great relief and contentment to the Vietnamese refugees who were landed there. Setting foot on ‘terra firma’, having a shower, getting a change of clothes and receiving assistance from voluntary agencies – I have no doubt these poor, poor people would have thought they were in seventh heaven. Added to this was the relief of knowing they would not be pushed back out to sea. The then Secretary of Security stated ’I do not believe it would be right, or to Hong Kong’s credit, to send out to sea a heavily loaded ship on the basis that they can take their chance somewhere else.’ I believe it is to Hong Kong’s eternal credit that this policy was adopted and I know that those of us who were in the ’front line’ would not have had it any other way. That said, the ever-increasing boat arrivals put a tremendous strain on those whose job it was to find and organise accommodation as existing space reached saturation point.

It verges on the paradoxical, but I have a sense that the combination of the stress we all suffered and the wonderful cooperation between all the organisations involved was a recipe for nervous breakdowns. Perhaps this example will give a hint of what I mean: When I contacted a young lady in the Immigration Department as yet another crisis presented itself, she said to me, ’Wait while I go into hysterics’.

It was essential that one did not become ‘emotionally involved’: had we done so, nervous breakdowns would have been legion. The alternative, which I believe we all suffered from, was ‘compassion fatigue’. But our suffering was as nothing compared to that of the refugees. I earnestly hope that such a heartless human holocaust might never again be visited on any people anywhere. Here I quote from The Economist of 21 July 1979: ‘With 1 million living refugees since [the fall of Saigon on 30 April] 1975 and maybe another 3 million to come, plus eventually up to half a million corpses in the South China Sea, the enforced exodus from Indochina already ranks with what the Ottoman Empire did to the Armenians, Hitler to the Jews and Stalin to the objects of Soviet displeasure.’ This perhaps explains, far more eloquently than I ever could, what we were confronted with.

Among particular cases of awfulness recorded in my diary, one stands out. On a boat that arrived with just a handful of refugees I saw a youth of some fifteen years tethered to the mast. Interrogation of the boy revealed that he had been due to be eaten, but was spared this fate by circumstances. Later I found out that he’d been tethered to the mast because they were afraid he might jump overboard and so deprive them of their food supply!

Among particular cases of awfulness recorded in my diary, one stands out. On a boat that arrived with just a handful of refugees I saw a youth of some fifteen years tethered to the mast. Interrogation of the boy revealed that he had been due to be eaten, but was spared this fate by circumstances. Later I found out that he’d been tethered to the mast because they were afraid he might jump overboard and so deprive them of their food supply!

Dao Van Cu (for that was the lad’s name) said that a few days earlier the others had held a discussion among themselves and then gathered around him. They’d pulled his shirt over his head and tied his legs with a rope. While two men pinned him on the deck, the captain’s nephew beat him over the head with an iron bar until he bled profusely. As he lay bleeding, he heard one of the others tell a third to cut his throat. He cried and pleaded for mercy ‘They wanted to eat me,’ he said, ’and had a large pot of boiling water ready. I waited for them to cut my throat’.

No-one stepped forward to kill him and he was left lying in the bow. Later that day, his ailing young companion died and was eaten by the others, and he said this gave him respite. But two days later the threats were renewed. His life was spared, he said, only because their boat arrived in Hong Kong territory.

This story subsequently appeared – on 13 August 1981 – as an article in the New York Times by Henry Kamm, the newspaper’s Asian Diplomatic Correspondent.

Other crises we had to deal with were the rapid evacuation of refugee boats from WQA as storm signals were hoisted. At these times one could not but reflect on how so many of these poor people, in their flimsy overloaded boats, would have been perishing in unimaginably horrific circumstances. The reference in The Economist to ‘anything up to half a million corpses in the South China Sea’ can assuredly amplify what I am trying to convey.

My narrative cannot pass without reference to two of many vessels we had to deal with. One was an oceangoing Panamanian-registered freighter named Skyluck that is the subject of a story by Jon Davison elsewhere in this volume. The other vessel was a dreadful hulk named Ha Long, which arrived on 15 April 1979. This 35-metre-long vessel, built to hold 30, had 573 on board. To say they were ‘packed in like sardines’ would scarcely do justice to their situation. They were in tiers – men, women and children jammed in and not able to move. One could only wonder how they survived the voyage.

My diary records that I actually boarded the Ha Long on 19 April, though how I managed to find somewhere to put my feet should have had a Guinness Book of Records entry. So awful were the conditions on this boat that refugees were ‘fast tracked’ and disembarked two days later. Looking back on the incident now, my first reaction is to feel that it was heartless to leave these poor souls on board for as long as six days. But, as I have said, this was just one case of awfulness, no worse than many others.

Talbot Bashall

This story excerpted from the book "Boat People, personal stories from the Vietnamese exodus 1975 -1996" edited by Carina Hoang

Related Articles

A Cluster of Pickerel Weeds

Time has gone by quickly. It has been 21 years living in this new country where our children have grown up. I have often told them the story of our trip, including the selfishness of that young man. I often remind myself that we must try hard to make the former “cluster of pickerel weeds” enrich this land which is our second homeland.

The girls, the girls! Hide the girls!

We were old enough to hide ourselves, and we jumped up at once and scrambled to a place where they could not see us. There were two of them, and through my seven-year-old eyes I could see they were armed with swords that gleamed mercilessly in the sun as they jumped onto our boat…

Live to Tell Our Tale

Since escaping Vietnam 25 years ago, my mind has constantly wandered back to two sisters – two of a dozen on my boat who were raped, tortured and stripped of their dignity. As a young man, I had never felt so helpless. I often wonder if those women have been able to get on with life.

My Mother

After the fall of Saigon, things changed drastically for our family under the communist regime. Wanting a better life for their children, my parents decided we would escape from Vietnam by boat, but not all together.

I Was Sixteen and I Was Lost

By: Lala Stein I had in my possession a little bag filled with memories and hopes. I was heading south, to Chau Doc, in the company of a small group of people with the same purpose: we were seeking freedom. After about a week in Chau Doc we managed to get on a ferry...

My Journey

By: Don Thu Nguyen When the communists took over South Vietnam I had just graduated from the military officer training school. Because I had not served in the military I was spared from going to re-education camp, but my background meant I had no chance of securing a...

My Children

By: Lyma’s mother For six months I lived on one bowl of salty rice a day. I was a prisoner, jailed because some policemen concluded I was a CIA agent because they found a photograph of me with an American. I explained that he had been my English teacher, and the photo...

The Endless Journey of An Exile

After the incident in 1975, there was a strong cross-border wave in Vietnam. There were many escapees who crossed the border by sea or by land, but the most common means of transportation was by sea…

Vietnamese Boat People in Australia

In April 1975, the North Vietnam Communist Government invaded South Vietnam. The Southern Vietnamese people could not live under the Communist regime so they later found their way for freedom…

Goodbye Grandma

Poor Grandma, she’d made the boat journey but could not survive once she got to the island. I carried her once more, this time to the jungle to bury her. She’d known that she might not make it…